Protecting forests, biodiversity and the rights of indigenous peoples: an example from the Amazon and the Congo Basin

General statement by Johannes Schwegler for the public hearing held by the Committee for Economic Cooperation and Development (AwZ) of the German federal parliament.

In TREEO’s opinion, protecting, conserving and sustainably managing wild tropical forests is not only urgent but absolutely necessary if we want to stop climate change, neutralise dangerous tipping points, preserve biodiversity for future generations and protect forest regions for the people who live there. Forests – and more broadly their soil and vegetation – can immediately provide the infrastructure for Carbon Capture and Storage (CCS), supplementing the massive reductions in CO2 emissions in industry, transport and energy production. The next 10-30 years are crucial for the climate, and CCS could still set a course that slows down or even stops climate change, or that extends the window of opportunity in which we can still take action. The green potential of CCS must be recognised and promoted on the political stage, which would require a concerted and coordinated effort by political actors, in particular the donors and implementing organisations that work alongside partner countries in various international funding instruments such as GEF, WB, Green Climate Fund, etc. It is equally important to realise that national forest development, especially in the tropics, cannot be bound to three-year project phases. Instead, this development must be linked to processes in which relevant actors undergo changes that require a 10, 20 and quite possibly 30-year time frame.

There are three prominent examples from the distant and more recent past which reflect the global efforts toward global forest conservation and the effective protection of tropical forests: the Tropical Forest Action Plan (TFAP) from the 1980s and 1990s, initiated by the FAO and the forest sector; the Merck-INBio contract model agreed between Costa Rica and the pharmaceutical company Merck concerning the use of genetic resources at the beginning of 1990 as an innovative initiative of the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD); and the REDD+ Mechanism of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) from 2010.

In addition to reducing global CO2 emissions and protecting and conserving tropical forests, forest landscape restoration (FLR) also shows enormous potential for development and should receive equal attention. The idea of using FLR to complement the protection and conservation of forests was brought to the international political stage by the Bonn Challenge in 2011. Launched by the German Federal Ministry for the Environment (BMUV) and the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), the Bonn Challenge is a platform to discuss and implement strategies related to the reconstruction of forests. Through its AFR100 initiative in Africa, the German Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development (BMZ) also supports this approach. The United Nations Decade on Ecosystem Restoration (2021-2030) is a result of this platform and, together with various Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), it offers TREEO the political framework to enact positive change.

As with the protection, conservation and sustainable management of forests, there is no one-size-fits-all solution for restoring forests and forest landscapes. The German forestry industry understood this, as demonstrated by their “Iron Law of Site Conditions”. A large toolbox of approaches, examples and experiences can be applied depending on the location and the expectations of the various stakeholders involved.

With that in mind, TREEO is developing its own innovative and creative strategy to reconstruct forests in Indonesia and Uganda. This initiative is guided by the "Ten golden rules for reforestation" published by World Agroforestry (ICRAF) in 2021.

For instance, TREEO has been planting fast-growing, native tree species in existing banana-coffee crops to improve agroforestry cultivation in pilot schemes in Uganda over the past several years.

The wood from these trees is intended for the timber construction sector (wood processing companies, carpenters etc.) where it will be used to produce laminated beams for national and regional markets. In this new strategy, smallholder structures are connected to the development of a wood-processing market approach. This approach circumvents the almost prohibitively high initial investment costs that farmers otherwise have to bear and it means that farmers do not have to wait several years for a return on their investments. Instead, existing crops provide the income required for subsistence, and by planting additional trees smallholders can supplement this income with very little effort.

Another way for small-scale farmers to generate income from their existing trees is the TREEO app. Developed over the past two years, the TREEO app makes it possible for smallholdings to easily record trees’ growth and CO2 storage.

TREEO’s main focus is to support rural structures, especially smallholder farms with the objective of creating a sustainable, green value chain that preserves the climate and biodiversity while also protecting and increasing the livelihoods of smallholders in the long term. With an increased amount of wood available, the construction industry has the opportunity to substitute grey building materials such as concrete and steel for timber. This approach assumes that pressure on existing residual forests would also be relieved or removed entirely, which could potentially lead to new network structures being formed between forest areas. The extent to which this strategy could be expanded to include the cultivation of insect/bee tree species and the cultivation of mixed forest structures is being investigated.

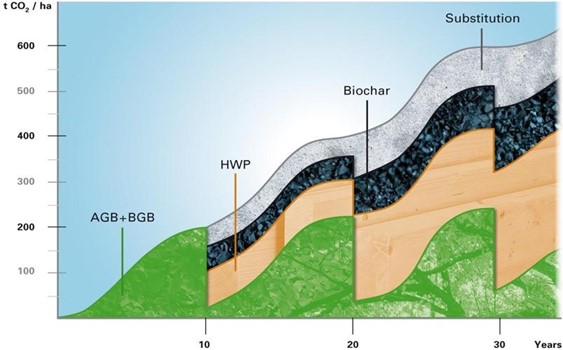

When considering the entire value chain – from afforestation to timber construction – four different carbon effects become apparent:

- Green: Carbon storage in biomass above and below the soil in a forest area – ten-year intervals between harvests

- Brown: Long-term carbon storage in wood products – here 50% of the wood is used for timber construction

- Black: Permanent carbon storage in biochar from wood waste used for organic fertiliser

- Grey: CO2 emissions avoided by substituting grey steel and cement

Summary:

- Forest conservation is extremely important and must be prioritised.

- Reforestation and timber construction must be considered together. We must take responsibility for the entire supply chain, produce raw materials for the circular economy and substitute out grey building materials.

- Smallholder farmers must be given top priority. CO2 standards must be based on their needs and most of the climate funds should reach the local actors.

- Confidence in nature-based climate solutions is only possible through strict monitoring. Full digitisation is a prerequisite for scaling.

- Our previous project cycles are too short. Forest projects need to run for at least 10 years.